'Biden's vision come to life' | Hanwha to invest $2.5bn in US solar manufacturing facilities

The South Korean firm will take advantage of new federal tax credits to create initial US production capacity for silicon ingots, and solar wafers and cells

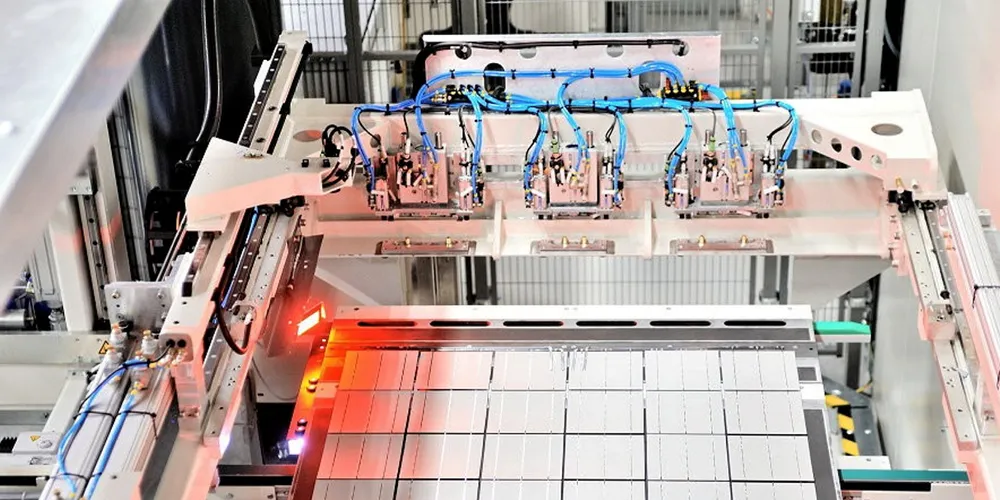

Hanwha’s Q Cells will invest $2.6bn in Georgia to create initial US manufacturing capacity for silicon ingots, and solar wafers and cells, and more than double production of modules in the state to 8.4GW a year.

The new facilities in Cartersville located 68km (42 miles) northwest of Atlanta will create a supply chain able to support 3.3GW of solar panels a year, while an existing factory in Dalton, 125km northwest of the capital, will expand module-making capacity by 2GW to 5.1GW a year.

The South Korean company’s investment is among the largest announced for clean energy in the US since President Joe Biden signed a landmark climate law last August containing at least several hundred billion dollars in medium- and long-term federal tax credits.

Thus far, most investments made public have been weighted toward module manufacturing facilities which the White House anticipated given the lower capital expenditure than other steps in the supply chain.

“We made the decision to take advantage of the US government's energy transition policies to maximize our competitiveness,” said Q Cells CEO Lee Koo-yung. “Our Solar Hub connecting Dalton and Cartersville will be North America's largest solar module manufacturing complex.”

“I think it's fair to say that this deal is President Biden's vision come to life,” said John Podesta, his senior advisor for clean energy innovation and implementation.

Biden lauded the move by Hanwha, estimating it would create “thousands of good-paying jobs in Georgia, many of which won’t require a four-year degree.” He added the investment will “bring back our supply chains so we aren’t reliant on other countries, lower the cost of clean energy and help us combat the climate crisis.”

Last April, Hanwha raised its ownership to 21.34% in Norway’s REC Silicon which intends to restart polysilicon production at a facility in Washington state.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) offers multiple tax credits to stimulate demand for solar energy and domestic supply chain manufacturing investment, as well as grants and loans with a major focus on re-purposing, re-powering, or replacing defunct energy infrastructure with clean energy led by solar.

The manufacturing-related tax credits that Q Cells expects to tap include the advanced energy product credit, known as 48C, worth 30% of capital investment to build, expand, or re-equip a manufacturing or re-cycling plant for solar equipment.

Another is the advanced manufacturing production credit, or 45X, that can be taken per unit of clean energy component (for select components) produced in the US and sold in a given tax year.

These components include central inverters, crystalline and thin PV cells, solar grade polysilicon, solar module assembly, structural fasteners, and torque tube and longitudinal purlin.

While the US is the world’s second largest solar market after China with installations having peaked at 23.6GW in 2021, it is heavily dependent on its global rival and countries in Southeast Asia for processing of solar materials and supply of components and finished panels.

Other shortcomings include limited ability to manufacture inverters and trackers, while there are only three US manufacturers of solar specialty glass in the US.

While the US invented silicon solar cells in the 1950s and dominated the global industry through the 1970s, leadership later passed to Japan and then China as manufacturers here could not compete with cheap and often state subsidized imports from there. By the early 2000s, most American firms had exited the business which was relatively small in scale.

The administrations of Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama from 2006 to 2017 focused mainly on using tax credits to stoke domestic demand for solar energy which was met largely with low-cost imports from Asia.

Obama initially did try to promote development of US solar technologies through the Department of Energy’s loan guarantee programme. Despite several successes, the initiative was burnt and became a political liability when thin-film solar company Solyndra declared bankruptcy in 2011 after DoE underwrote $535m in financing.

After 2014 until IRA, US solar policy has emphasised market development and scale and enforcement of tariffs on Chinese origin inputs and panels. The Covid pandemic and the Biden administration’s latent threat to slap duties on solar products China is allegedly exporting through Southeast Asia to avoid US duties have disrupted supply to here, hurt industry growth and raised costs.

The embrace by Biden and ruling Democratic Party of a central government driven US industry policy for clean energy has drawn criticism from opposition Republicans, who now control the House of Representatives in Congress, and the European Union, Japan, and South Korea.

Republicans contend that market forces should determine which energy technologies emerge and succeed, not White House political staff and federal bureaucrats, although they support public investment in basic and applied research by DoE.

The EU and Asian allies are concerned US subsidies are so generous and pervasive that private investment will exit their regions and they will fall behind with clean technology applications and development.

(Copyright)